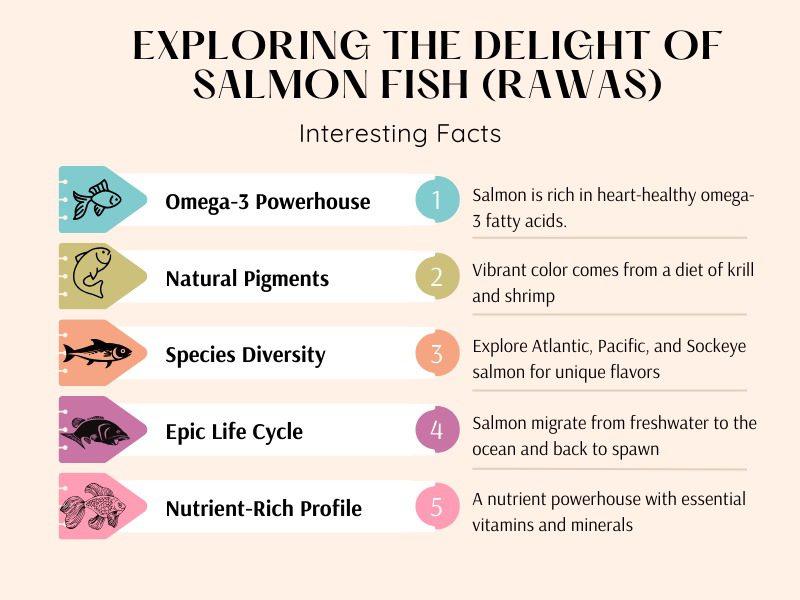

Since salmon migrate to the ocean as adults and live like sea fish, they are usually anadromous, meaning that they hatch in the shallow gravel beds of freshwater headstreams, spend their juvenile years in rivers, lakes, and freshwater wetlands, and then return to their freshwater birthplace to reproduce. Nonetheless, several species have lifelong restrictions to freshwater habitats, making them landlocked. According to folklore, fish spawn in the exact stream where they hatched, and tracking studies have mostly confirmed this. A certain percentage of a returning salmon run may stray and generate in other freshwater systems; this percentage varies according to the type of salmon fish type in Pakistan. Evidence has shown that olfactory memory is necessary for homing behavior.

Norway is the world’s largest producer of farmed salmon, followed by Chile. Salmon are essential food fish that are intensively farmed across the globe. Both freshwater and saltwater anglers highly value them as game fish for recreational fishing. Numerous salmon species have been introduced and naturalized in non-native habitats like the Great Lakes of North America, Patagonia in South America, and the South Island of New Zealand.

Categorization

Domain

Eukaryota

Kingdom

Animalia

Phylum

Chordata

Class

Actinopterygii

Order

Salmoniformes

Family

Salmonidae

Subfamily

Salmoninae

Types of Salmon fish

Atlantic salmon

Northern rivers on both Atlantic Ocean coasts are Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) reproduction sites.

Sebago, Onega, Ladoga, Saimaa, Vanern, and Winnipesaukee are just a few lakes where the landlocked Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar m. Sebago), a freshwater fish and potamodromous subspecies morph, inhabit. These fish in Pakistan migrate exclusively between freshwaters. Although they have independently evolved a life cycle exclusive to freshwater, they are not a distinct species from the sea-run Atlantic salmon. They will continue to do so even when they can access the ocean.

Chinook salmon

In the United States, chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) are also referred to as “king salmon” or “blackmouth salmon,” while in British Columbia, Canada, they are called “spring salmon.” As the largest salmon in the Pacific, chinook often reaches lengths of up to 6 feet (1.8 meters) and weighs up to 14 kg (30 pounds).In British Columbia, Chinook salmon weighing over thirty pounds are referred to as tyees. Additionally, large Chinook salmon were originally called June hogs in the Columbia River watershed. Chinook salmon inhabit chinook salmon as far north as the Mackenzie River and Kugluktuk in the central Canadian Arctic and as far south as the Central Californian Coast.

Chum salmon

The Russian Far East refers to chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) as keta, while some US states refer to it as dog salmon or calico salmon. The eastern Pacific, from Canada’s Mackenzie River to California’s Sacramento River, and the western Pacific, from Siberia’s Lena River to the island of Kyūshū in the Sea of Japan, are the regions where this species is most widely distributed among the Pacific species.

Coho salmon

Silver salmon is another name for coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) in the United States. This species can be found in British Columbia, Alaska, and Central California’s coastal waters (Monterey Bay). Additionally, the Mackenzie River is now known to experience it, albeit rarely.

Masu salmon

The Oncorhynchus masou, commonly referred to as “cherry trout” (sakura masu) in Japan, is a species of salmon found exclusively in the western Pacific Ocean, encompassing Korea, Japan, and the Russian Far East. In central Taiwan’s Chi Chia Wan Stream, there is a landlocked subspecies of salmon called the Taiwanese salmon or Formosan salmon (Oncorhynchus masou formosanus).

Pink salmon

In the western Pacific, pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), also known as humpback salmon or “humpies” in southeast and southwest Alaska, are found throughout the northern Pacific, from the Mackenzie River in Canada to the north of California and in the eastern Pacific, they are found in shorter coastal streams. The average weight of this Pacific species is between 1.6 and 1.8 kg (3.5 to 4.0 lb), making it the smallest.

Sockeye salmon

In the US (especially Alaska), ockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) are also referred to as red salmon. The eastern Pacific, which stretches from Bathurst Inlet in the Canadian Arctic to the Klamath River in California, is home to this lake-rearing species. The western Pacific, on the other hand, spans from the Anadyr River in Siberia to the northern part of Hokkaidō island in Japan. Sockeye salmon consume plankton that they filter through gill rakers, while most adult Pacific salmon eat small fish, prawns, and squid. Sockeye salmon that live in landlocked areas are called kokanee salmon.

Life cycle of salmon fish

Beginning

Salmon begin their lives as tiny, pea-sized eggs secreted beneath loose gravel in calm, clear rivers flowing into the North Atlantic Ocean. Despite all the odds, the parents of this little egg managed to spawn again in freshwater, finishing their life cycle and producing a new generation. To accomplish this, male and female adults stopped feeding as soon as they entered freshwater in response to gonadal development, focusing all their energy on procreation instead. Adults may begin migrating to suitable winter habitats up to a year before spawning occurs.

Although it can happen anywhere in a river, provided a suitable substrate of loose gravel is well-oxygenated, spawning usually occurs in headwaters. The female excavates a depression in the gravel with her tail to lay her eggs during the spawning season, which runs from November to January. One or more males release milt over them to fertilize the falling eggs. Swiftly, the female deposits gravel on the eggs, forming a ” redd ” nest on the riverbed several centimeters below the surface. The ova, buried deep in the gravel, are protected from predators like eels (Anguilla Anguilla), trout (Salmo trutta), and cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), as well as from the impact of debris carried by intense floods.

Ova

The water’s temperature affects how quickly eggs, or “ova,” develop. The eyes within the pea-sized orange ova are visible, and as the yolk sac containing food is consumed, movement becomes more noticeable. A female’s size affects how many ova she deposits in the redd; larger females weighing more than 10 kg deposit up to 15,000 ova total. This high fecundity (ova per female) is essential given the rare wild survival, particularly in freshwater environments. For instance, juvenile survival rates in the Burrishoole River on Ireland’s west coast ranged from 0.3% in 2001 to a high of 1.3% in 2007. This data was collected between 1970 and 2015.

Alevins

When the fish hatch in the spring, they are known as “alevins” and still have the yolk sac attached to their bodies. As soon as their yolk sac is absorbed, the alevins move through the riverbed’s gravel and become more active. The small fish must surface to breathe air once they are strong enough. They achieve neutral buoyancy by doing this, making it more straightforward to swim and maintain their position in swift-moving streams. As a result, this crucial time is known as “swim-up” and is when the young are first exposed to dangerous predators. They are referred to as fry once they can swim freely.

Fry

During the summer, the fins on the fry help them maneuver in the water and hold their position in swift-moving streams. The temperature, predation, pollution, and competition with other fry and fish species for food all affect the quantity of fryfed on microscopic invertebrates. Given their heightened sensitivity to variations in water quality, habitat, and climate, salmon are an excellent barometer of the health of both freshwater and marine ecosystems. Their presence in a river is considered a sign of a healthy aquatic environment.

Parr

As autumn progresses, the fry transforms into a parr with spots and vertical stripes for hiding. They live for one to three years, establishing their territory in the stream and feeding on aquatic insects. The parr goes through a physiological pre-adaptation to life in seawater by smelting once they reach a length of 10 to 25 cm. Their transformation into silvery creatures that swim with the current rather than against it makes this clear. Fish salt-regulating systems also undergo internal alterations. The smolt’s adaptation readies it for its voyage to the ocean.

Smolt

During the spring, many smolts, aged between one and three years, migrate from Irish rivers to the rich feeding grounds of the Norwegian Sea and the immense North Atlantic Ocean by following the North Atlantic Drift. Fish like capelin (Mallotus villosus), herring (Alosa spp.), and sand eels (Ammodytes spp.) are their primary food sources here. Fewer predators can consume them due to their rapid growth. Therefore, their growth rate is essential to their survival.

Adult salmon

Grilse, or mature salmon, return to their river in the summer after a year at sea, weighing between 0.8 and 4 kg. Salmon that require two or more years to mature at sea will reappear much earlier in the year, weighing between 3 and 15 kg, and will be highly sought after by fishermen due to their size. Pheromones, chemicals released by other salmon in the river, the earth’s magnetic field, and a high percentage of salmon’s “homing instinct” allow them to locate the river of origin. Perfect homing accuracy is anticipated even following migrations spanning over 3,000 kilometers to feeding grounds in West Greenland and the Norwegian Sea, north of the Arctic Circle. The return of adult salmon to rivers is a source of great excitement, with many being spotted performing aerial acrobatics and vaulting over waterfalls as they travel upstream. Before eventually finding safety in lakes and deep pools, salmon that manage to withstand the effects of pollution, poaching, and fishermen may still need to climb massive dams constructed across rivers. The life cycle recommences once they reach their spawning grounds amidst large boulders in the icy headwaters, guaranteeing the species’ survival for an additional generation.

Kelts

The salmon are called “kelts” after they have spawned. Due to their lack of food since entering freshwater and their need to expend energy for proper reproduction, kelts are vulnerable to illness and predators. After spawning, mortality can be high, particularly for males, but some do make it through and resume their fantastic journey. Similar to tree rings, the rings deposited on scales were initially used by scientists studying salmon to estimate the age and growth of the fish both in freshwater and in the ocean.

They proved that some kelts could spawn three times by doing this! A zero-sea winter salmon is an Irish salmon that matured in less than a year at sea, setting a new record. The salmon returned from the sea on May 11, 2007, weighing 810g, leaving the Bundorragha River in County Mayo on April 27, 2007, as a 1-year-old smolt.

Diet

Salmon are mid-level carnivores, and their food type depends on their life stage. Up until they are fingerling size, salmon fry mostly eat zooplankton. After that, they eat more aquatic invertebrates, including worms, microcrustaceans, and insect larvae. When younger (parrs), they develop more excellent predatory instincts and actively hunt small bait fish, tadpoles, small crustaceans, and aquatic insects. They are also known to eat fish eggs, even those of other salmon, and to breach the water to attack terrestrial insects like grasshoppers and dragonflies.

When they reach adulthood, salmon act like other mid-sized pelagic fish, consuming a wide range of marine life, including smaller forage fish like mackerels, sand lances, lanternfish, and barracudina. They also consume polychaete worms, squid, and krill.

Mythology

Mythology

In many Celtic mythology and poetry branches, the Salmon is a significant animal frequently connected to venerability and wisdom. According to Irish folklore, fishermen believed that naming Salmon after fairies would bring misfortune.[130] A creature known as the Salmon of Knowledge[131] is significant in Irish mythology’s story The Boyhood Deeds of Fionn. In the story, Finn Eces, a poet, searches for a salmon for seven years, believing that eating it will bestow knowledge upon its eater. When Finn Eces finally catches the fish, he hands it to Fionn mac Cumhaill, his young apprentice, to cook for him. But Fionn accidentally burns his thumb on the Salmon’s juices and puts it in his mouth out of instinct. He unintentionally acquires the wisdom of the Salmon by doing this. The Salmon has also appeared in other places in Irish mythology as incarnations of Fintan mac Bóchra and Tuan mac Cairill.

Native American mythology along the Pacific coast, from the Haida and Coast Salish peoples to the Nuu-chah-nulth peoples of British Columbia, places a solid spiritual and cultural emphasis on Salmon.